Research

University of Windsor, 2020 ~ Present

I am a PhD candidate at the University of Windsor, under the supervision of Dr. Dan Mennill. I study a population of Savannah Sparrows that breed on Kent Island, New Brunswick, Canada, a small island in the Bay of Fundy. I study how song and other vocalizations are used throughout the breeding season.

I record birds in their natural environment and find and monitor nests for my research, as well as to add to the ever-growing long-term Savannah Sparrow project on Kent Island, at the Bowdoin Scientific Station.

I study how song relates to reproductive success. Savannah Sparrows are socially monogamous, however, many pairs also seek extra-pair mates and produce extra-pair offspring. I measure many features of male song and compare these to both the social success of males (how many offspring each male raises) and the genetic success of males (how many offspring each male sires). I hope to shed light on which song features reveal male quality and which are important for mate choice.

Going a step further, I am also investigating if male song features can predict future mating effort or parenting effort of males. Females must choose social and extra-pair mates early in the breeding season. To avoid choosing males who do not help with parental duties, females may be able to assess male parental behaviour through song.

I measure song features, song rate (as a proxy for mating effort), and male feeding rate (as a proxy for parental effort). I measure feeding rate using small cameras at the nests, watching each male and female arrival to the nest with food. By comparing song features to mating and parenting effort, I can look for evidence of a parenting-mating trade-off, where males invest differentially in mating or parenting effort, depending on their quality.

While watching nest watch videos, I observed an interesting behaviour by many of the adult pairs. When both adults were at the nest site, the departing adult often produced a distinctive “twitter call”, that I had not heard used before.

Vocalizations are risky to make at nest sites, because they can be heard by nearby predators. Even so, many species produce calls at the nest site to simulate nestling begging, and thereby make feeding more efficient, or to communicate with their mate, possibly negotiating parental duties, or communicating nestling needs.

Through observational and experimental research, I am investigating possible functions of this “twitter call” in the context of provisioning behaviour.

Savannah Sparrows are a species of the Passeriformes order. As a songbird, individuals learn their vocalizations early in life, by listening to and imitating nearby adults. From previous research on this population, we know that the most important time for song learning is during the individual’s first summer (within weeks of hatching) and at the onset of the first breeding season (less than a year old).

To learn more about song learning in this species, I am investigating if the quality of the acoustic environment of nestlings impacts later learned song quality. Savannah Sparrows on Kent Island are highly philopatric, making it possible to study individuals on the breeding grounds from birth to death. Specifically, I want to know if nestlings that are exposed to more tutors, or tutors with higher quality songs, learn to produce higher quality songs as adults the following year.

To understand how the nestling acoustic environment influences learned song, I first needed to know how far nestlings can potentially hear tutors from the nest. Savannah Sparrows build their nests on the ground, under cover of dense vegetation. Vegetation is known to reduce sound transmission, so I expected the nestling acoustic environment to be limited in comparison to the adult acoustic environment.

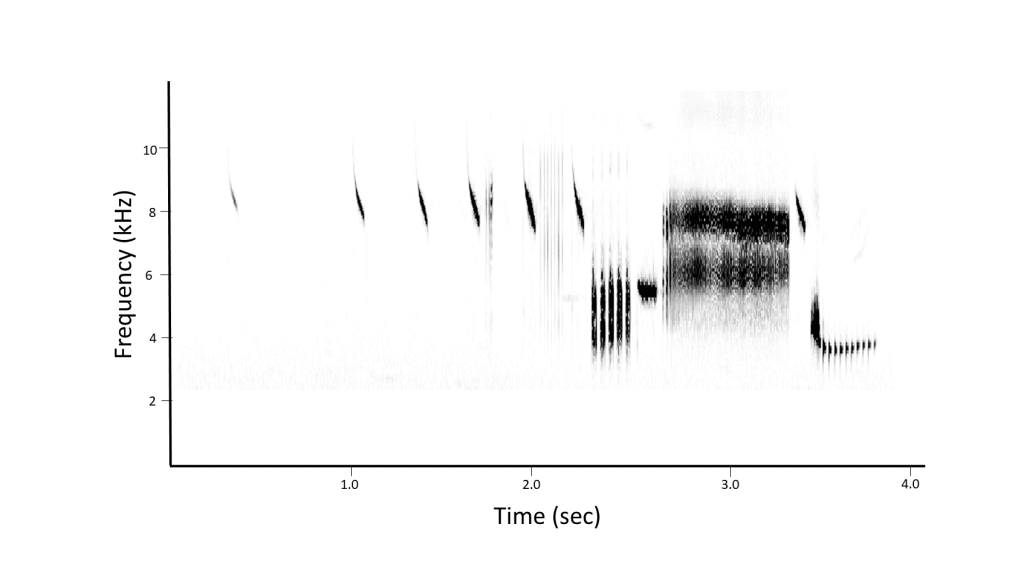

I tested sound transmission into the nest by recording naturally singing Savannah Sparrows using two microphones: one placed about 1m above the nest, at a typical singing height, and the second placed directly inside the nest, facing the same direction. Each song was recorded simultaneously by each microphone, so I was able to directly compare songs above and within the nest and determine at which distance songs become undetectable from the nest. We found that songs are much quieter when heard from inside the nest than above and conclude that the nestling acoustic environment reaches a maximum of approximately 78 m. Read more in our 2023 Avian Research publication.

Finally, I investigate if adult birds facilitate vocal learning through nest site selection. I test multiple hypotheses about nest site selection, including predator avoidance, facilitating extra-pair copulation, and I propose a new hypothesis that females select nest sites within their territory that maximize offspring vocal learning by positioning their nestlings closer to singing neighbouring males.

I hope to find evidence that vocal learning is influenced by the nestling acoustic environment, and that adults actively maximize the acoustic environment for their offspring through nest site choices.